Why do politicians act the way they do?

This is the simple question (with a somewhat lengthier answer) that Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith attempt to answer in The Dictator’s Handbook. Aimed at anyone who is interested in understanding the logic behind political decisions, the authors take a common sense approach in explaining some of the most important questions about modern politics.

First published in 2011, the book is primarily based on The Logic of Political Survival, another book first published by four professors (including de Mesquita and Smith) in 2003. The Dictator’s Handbook itself explains what has been dubbed “selectorate theory”, in a more accessible and easily understandable form than their original, more academic book.

The Dictator’s Handbook certainly succeeds in providing answers to the questions it poses, in a way that is refreshingly dissimilar to other books in the “politics explained” genre. Some of the topics addressed are:

- How does an aspiring leader gain, and maintain, power?

- What do multinational corporations and dictatorships have in common?

- Is democracy a luxury?

- Why are rebellions so infrequent in counties ruled by the harshest and most tyrannical leaders?

- And, when such leaders are finally deposed and replaced, why does the new leader often seem to be even worse than their predecessor?

The role of corruption, loyalty, foreign aid, and oil, are all factored into the thoroughly researched and well reasoned explanations to these questions. And while many relevant examples are used to illustrate the points made, “politics through storytelling”, as the authors call it, is avoided.

A more comprehensive way of looking a politics is favoured, as the authors argue that treating every political event, be it the outcome of an election or the commencement of a revolution, as a “one-off, one-of-a-kind” event is unhelpful and misleading. They argue that it is possible to find some simple rules that explain why leaders make the decisions they do, both in the harshest dictatorships and the most progressive democracies alike, as human nature remains consistent, regardless of which political system is prevailing at the time.

A more familiar way of thinking about politics – with a larger focus on the ideologies of governmental systems and political candidates – is dispensed with, and a new way of thinking about governments is introduced. De Mesquita and Smith argue that all aspiring leaders really just want to gain and maintain power for their own personal benefit, and to do so, they must manipulate the political system in any way they can. However, no matter what governmental system is in place, they must all contend with the same three groups of people if they wish to gain power:

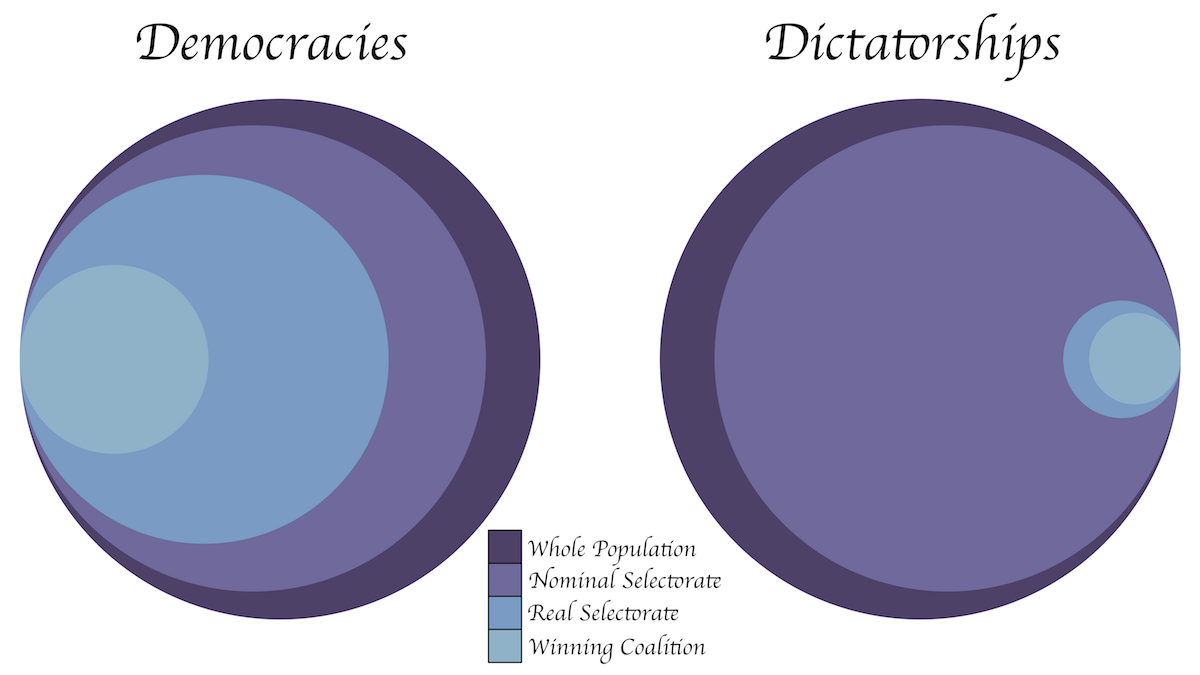

1 – “The Nominal Selectorate”

This group consists of people who could have a say in who the next leader is, democracy, this is everyone eligible to vote – usually a majority of the population. In a dictatorship, this group may also be very large – everyone can have a say, but in reality it will count for nothing. The members of nominal selectorate are interchangeable – a pool of potential support for a leader.

2 – “The Real Selectorate”

This group consists of those people who actually have a say in who becomes the next leader – those who actually turn up to vote, in a democracy. In a dictatorship, the real selectorate consists of those few regional leaders and generals who really have a say in who should become the next leader. The members of real selectorate are influential – they can actually alter a leader’s chance of gaining power.

3 – “The Winning Coalition”

The winning coalition is the minimum number of essential supporters (from the real selectorate) required to maintain power. In the UK, for a party to win a general election, the party must have at least half the number of seats in parliament. As a seat is won when just over one half of the real selectorate of one constituency votes for that candidate, just over one quarter of the real selectorate vote is all that is required to come to power. This is the winning coalition – the minimum number of people who must be kept content for a leader to gain power. In dictatorships, this winning coalition may be tiny, consisting of a few hundred people at most, maybe only a few tens in certain countries. The members of winning coalition are essential – without them, the leader cannot gain power.

By understanding how the differing relative sizes of these three groups affects how leaders can come to and maintain power, we can understand why politicians make the decision they do.

A Typical Democracy

If the population of a democratic country is 100 people, the nominal selectorate, those who are eligible to vote, may be 80 people. The real selectorate, those who actually turn up to vote, may be only 50 people – a 63% turnout (A fairly low turnout for a country such as the UK). And as only a quarter of the real selectorate are required to come to power, the support of only 13 people (provided this support comes from the correct regions) is required to rule over the entire population.

A Typical Dictatorship

In a hypothetical dictatorship with a population of 100 people, nominal seletorate, real selectorate, and winning coalition all remain, but in different proportions. The nominal selectroate may still be very large – 80 people may still be eligible to vote, as in our hypothetical democracy. Even if the election is a sham, the nominal selectorate is still large. Unlike democracies however, only 5 may make up the real selectorate – a few generals and regional leaders may be the only people who have any real say in who gains power. The winning coalition will be even smaller – only 3 people from the real selectorate may be needed to come to power.

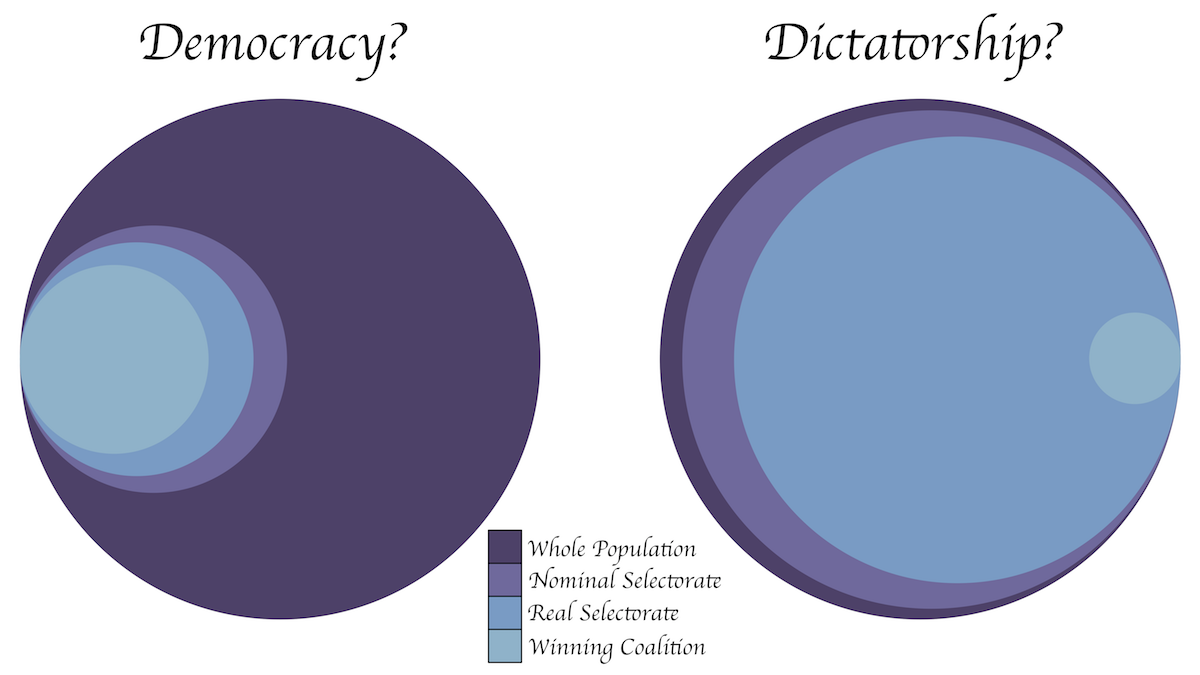

This is certainly a novel way of thinking about different governments. The distinction between democracies and dictatorships becomes blurred, as it is not obvious how many people can be part of the nominal selectroate, real selecorate, or winning coalition before a dictatorship becomes a democracy.

However, according to de Mesquita and Smith, the size of the winning coalition is by far the most important factor in determining how a government, and its members, behave – what a leader’s ideology is, or whether they are a “good” or “bad” person is irrelevant. Instead, the authors assert that the means by which leaders maximise their chance of holding onto power is different in dictatorships and democracies due to the differing sizes of the winning coalition, and so the behaviour of those in power alters according.

This leads to my main criticism of The Dictator’s Handbook. De Mesquita and Smith make a key assumption about all leaders, which is perfectly summed up by the epigraph of the final chapter. The quotation, from J. P Morgan, reads “A man always has two reasons for doing anything: a good reason and the real reason.” As seen through the lens of selectorate theory, this real reason – both for ruthless dictators and democratically elected prime ministers – is a desire to stay in power, to allow the leader to accrue personal benefits to themselves. The “good” reason is totally irrelevant – differences in ideological stances between political candidates are merely details.

So why do some politicians seem to genuinely care about the welfare of the people? De Mesquita and Smith’s explain “good” behaviour in politics like this. In democracies, the best way to maintain power is normally to act in a way that aligns with the interests a majority of the general population – hence democratic countries tend to offer education, healthcare, and other public services, due to the large size of the winning coalition. In dictatorships on the other hand, the best way to stay in power is to please only a few very powerful individuals. Consequently, dictators often do not spend any time or money on improving the standard of living for the general population, instead attempting to keep only those few essential backers happy. The authors conclude, therefore, that no leader really does what he or she believes to be right, but merely does what will please the winning selectorate – those people who are needed to gain and hold onto power.

While many would certainly agree that a desire for power is all that drives many world leaders – who seem to change their passionately held beliefs overnight to become more aligned with public opinion – the motivations of leaders such as Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela are also assumed to be the same.

All the arguments presented in the book are well reasoned and methodically explained, apart from this underlying assumption, which, while acknowledged, is never addressed in the detail that an assertion so central to the theory merits. Maybe it is a fair to say that all leaders, or at least the vast majority of them, operate out of pure selfishness, but that topic certainly merits a chapter, if not a book, of its own – I’m certainly not the only one who has noted the lack of concern given to this issue.

If there is another negative aspect about The Dictator’s Handbook, it is the occasional lack of focus in certain places. In some chapters, many different topics are touched upon briefly, and while most of them are returned to and picked up later in the chapter, this can sometimes be confusing, in an otherwise very understandable and comprehensively explained book.

For the most part however, The Dictator’s Handbook is nevertheless an intelligently written and understandable introduction to why leaders – whether CEOs, presidents, or dictators – act the way they do. Although it presents a somewhat unconventional theory of politics, the argument de Mesquita and Smith, backed up with copious examples, certainly provides plenty of reasons to believe that “the cynical analysis is the true one”.

Worth your time?

I also highly recommend GCP Grey’s video, The Rules for Rulers, which provides a useful summary of the book. I watched it before reading the book, and it can sometimes help you to see what the author’s are getting at, when they seem to wander from the topic at hand.